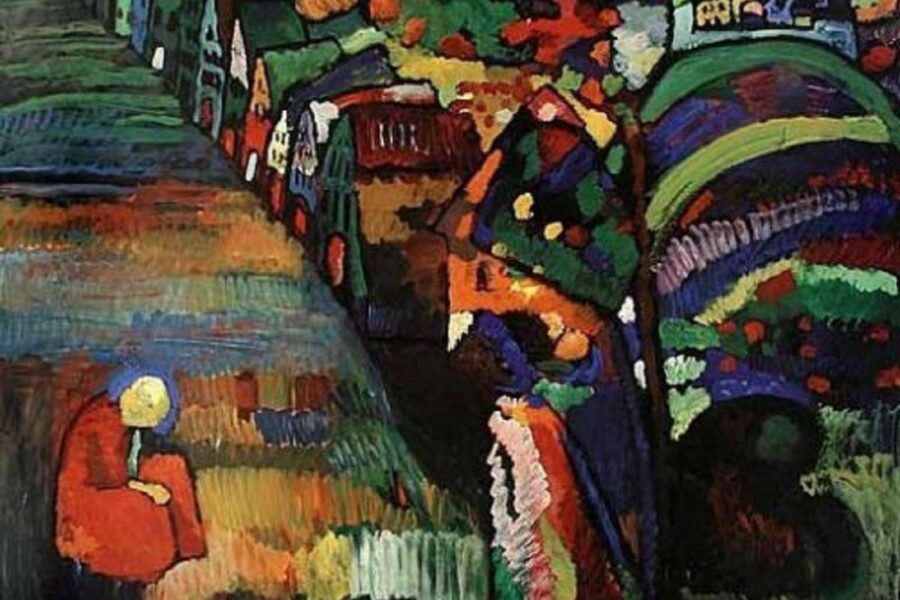

At the sad record of the Nazi spoliations, this work is certainly not at the top of the list. Neither the most beautiful nor the most expensive. First Day of Spring in Moret, a canvas painted in 1889 by the Impressionist artist Alfred Sisley, was sold at Christie’s in New York, in May 2008, for the sum of 350 000 dollars. Far from, for example, the 135 million dollars reached in 2006 by another painting stolen from its Jewish owners, such as the famous Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, by Gustav KLIMT.

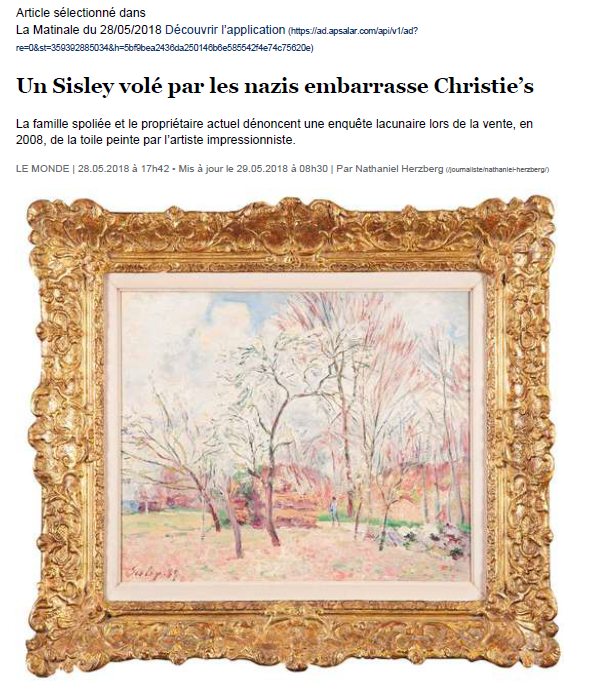

Yet this small painting promises to take a special place in the history of restitutions. The family looted of its property during the Second World War and the gallerist who holds the painting accuse the auction house of not having carried out the necessary checks. “It is not serious to claim that Christie’s, which has a specialized service in the search of looted artworks, has been able to ignore the origin of such a painting,” as stated in its complaint filed in August 2017, before the Paris court, as stated by the Grandson of the owner, Denis Lindon.

In the Lindon family, Denis is not the most famous. His brother Jérôme, founder of the Editions de Minuit, marked the history of the French edition. His nephews, comedian Vincent and writer Mathieu, regularly occupy the cultural pages of newspapers. “But I am the oldest surviving heir, one of Alfred Lindon’s last two grandchildren,” explains this former entrepreneur, who became a professor at HEC. At 91 years of age, I have free time, so it seemed normal for me to take care of it… I was very attached to my grandfather. He allowed me to spend a year at Cambridge, he who had not (even) studied.”

Alfred Lindon’s trajectory is a snapshot of the self-made-man

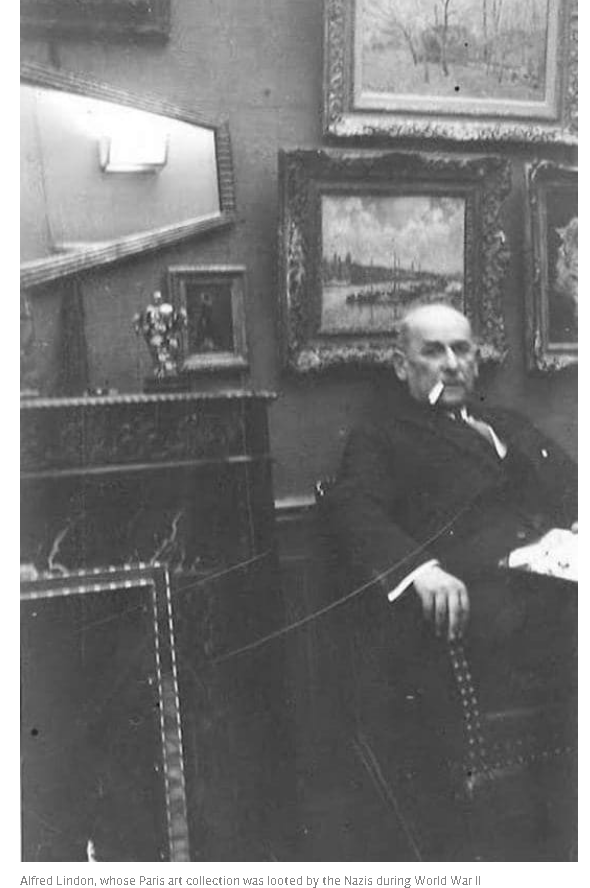

Alfred Lindon’s trajectory is a cliché of the self-made man. Born in Krakow, Poland, in the 1870s, he was then called Lindenbaum and at the age of 3 he arrives in London. The family is poor. At the age of 13, he began working for a distant diamond parent company, where he climbed the ranks. Fascinated by pearls, he became an expert and made a fortune. When the market collapses with the production of cultured pearls, he changes to gemstones, always successfully. He married the daughter of an immigrant Dutch diamond family in France, Fernande Citroën – the sister of the car manufacturer – and moved with her to Paris. In 1917, his patriotism and evident “antigermanism” led him to change his name.

His financial success allowed him to cultivate his passion for paintings. He himself held a paintbrush, “but he said he had no imagination, so he copied from memory the paintings he had observed at the Louvre,” recalls his grandson. Little by little, he accumulates a collection of paintings, engravings and miniatures of various eras, with a marked preference for the Impressionist period.

64 Paintings at Chase Bank

When the war broke out, Alfred Lindon protected his family in the free zone of France and stored sixty-four of his paintings – the most important – at Chase Bank, at rue Cambon (in the 1st arrondissement of Paris). He was fortunate to have escaped to New York. In November 1940, the Nazis forced open the vaults of the bank and seized the Monets, Renoir, Degas and other Cézanne paintings. On December 10, 1940, they are recorded at the National Gallery (in Paris), where the looted works of the Jews are stored.

Upon the liberation of France, Alfred Lindon sent the Commission for the retrieval of artistic works an inventory of his missing artworks. He will find the essential ones. “My father kept looking for the ones that were missing, but he didn’t tell us about it,” said Denis Lindon. I was convinced that this was all over. Until the Ottawa museum calls me. In 2006, the Canadian institution, which decided to check the provenance of all its paintings, discovers that an interior of Vuillard appears in the register of deprived goods held by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The name of the owner is indicated.

Alain Dreyfus, buyer of the painting: “When you buy at Christie’s, you cannot imagine that the work has such a vile past”

This restitution, widely commented across the Atlantic, stirs up the interest of the world. This Canadian company has made a speciality: to recover, for remuneration, the works stolen during the war. It offers its services to the fourteen Lindon heirs. The French descendants refused its advances, but the Anglo-Saxon branch, scattered from Canada to Australia, agreed. It is the founder of Mondex, James Palmer, who first finds traces of the painting of Sisley painting. “One of my American cousins wrote me to advise me,” Denis Lindon recalls.

The work is in the Dreyfus Gallery in Basel. Its owner, Alain Dreyfus, acquired it on November 6, 2008, at Christie’s in New York, for 357 000 dollars. During this impressionist auction, the former collector of stamps, who became a painting dealer, also won two paintings by Renoir and Boudin. “I didn’t even think about checking the provenance,” he says. When you buy at Christie’s, you cannot imagine that the work has such a despicable past. How could they let that happen? The lawyer of the French branch, Antoine Comte, adds: Christie’s runs the specialized symposia to explain that they are leading a constant vigil. The truth is that they did nothing to know where the painting came from.”

“All appropriate searches”

At Christie’s, we have a completely different outlook of this story. “We conducted all the appropriate research possible in 2008,” says Catherine Manson, who is responsible for the communication of the Auction House. In particular, we consulted the artist’s catalogue raisonne and the essential databases, including the stolen property directory. But at the time, there was nothing to bring this work closer to the plaintiffs.”

This assertion deserves careful consideration. First, the record presented by Christie’s at the time of the sale: between the acquisition of the painting in 1923 by the Parisian gallerist Perdoux and its sale “around 1972” by the merchant Daniel Wildenstein, does not provide any information. “Such a hole (in the provenance) is an immediate warning, especially when the post-war seller is called Wildenstein,” says lawyer Corinne Hershkovitch, Spoliations’s business specialist. The Franco-American gallery Wildenstein has indeed found itself involved in several cases of deprived paintings.

Back to the famous databases. The painting is not actually listed under its title in the stolen property directory. “On the other hand, the catalogue contains three paintings by Sisley mentioning the name “Spring”, details James Palmer, the President (sic) of Mondex. One of them is accompanied by a different photo, which eliminates that one. There are two left. One claimed by Mr Lindon and Christie’s is well acquainted with the Mr Lindon, since they sold the Vuillard (which was returned) by the Ottawa Museum in 2006.”

Another available record is at the NARA archives (National Archives and Records Administration) in Washington, D.C., which lists some 20,000 stolen works in Paris during the war. The Lindon collection is found in microfilm number 12, as shown in the summary. And, under the label Li-56, a “Spring Landscape” appears, with this time the same dimensions as the Christie’s painting. Any more doubts? It was then (simple) enough for the auction house to ask its representative in Germany to go and consult the Federal archives in Koblenz. This time they would have found not only the entire description (dimensions, technique, and author), but above all the full title and even a photo of the artwork.

Exchange of money for Göring

They could have even discovered some picturesque details. Thus, upon its arrival at the National Gallery, the (art) collection of the “Jew Lindenbaum” was reserved for Hermann Göring. Not just the number two of the (Nazi) regime who appreciates impressionist art. But these “degenerate” works could be used as a bargaining chip. A report of the French services of 1945 indicates that on July 9, 1941 eighteen of them, including the Spring Landscape, were bartered against a Titian (painting) that had just been acquired by Gustav Rochlitz, to the delight of the German merchant. We do not know what he did with the artwork.

Now a negotiation will begin. The Lindon (family) wants their painting back. Alain Dreyfus has “no problem doing so, provided that Christie’s compensates me”. He is claiming the price he paid himself “plus 8% a year”. It seems reasonable: they (Christie’s) require 16% for any delay. The gallerist is all the more determined as the Swiss police have seized the painting. “It’s in my trunk, but I don’t have the right to do anything with it. I’m a stuffed turkey.”

For the time being, Christie’s believes that “the legal action in progress is between the owner and the heirs”. Will it hold this position long? What will the French judiciary decide? And what about American justice, where a sales record was just broken a few weeks ago; what if for similar reasons these artworks were in turn seized? The little (Spring) Landscape has not finished speaking yet.