This is an English translation of the original French Article FRENCH ARTICLE “Une loi pour la restitution d’œuvres d’art spoliées par les nazis : une première en France” on France24 on February 15, 2022.](https://www.france24.com/fr/culture/20220215-une-loi-pour-la-restitution-d-%C5%93uvres-d-art-spoli%C3%A9es-par-les-nazis-une-premi%C3%A8re-en-france)

Published on :02/15/2022 – 17:23

Text by: Bahar MAKOOI Video by: FRANCE 2 Time:8 mins

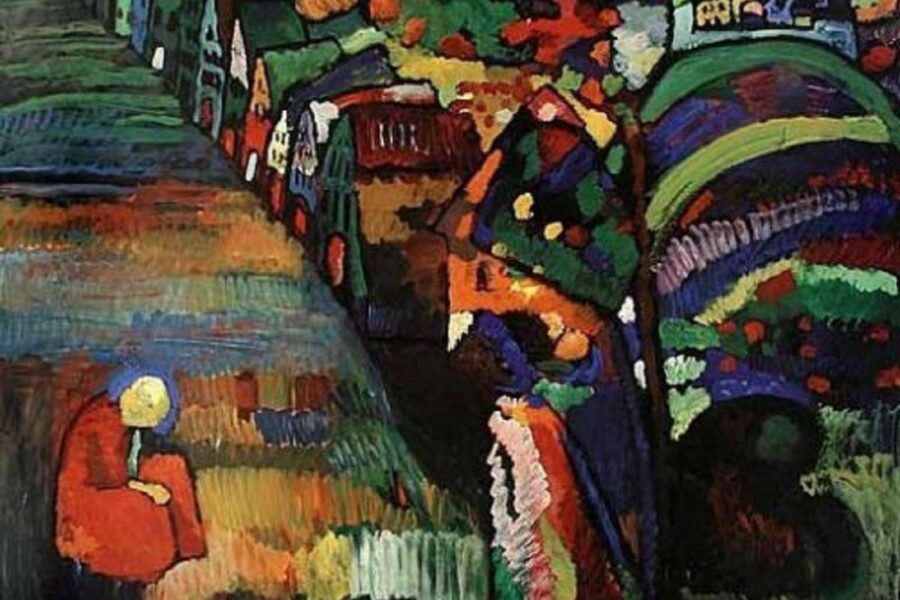

The French Minister of Culture, Roselyne Bachelot, in front of “Rosiers under the trees” by Gustav Klimt, March 15, 2021

Fifteen works looted by the Nazis from the national collections of France will soon be returned to the Jewish families to whom they belonged. After the National Assembly, which gave its consent at the end of January, the Senate approved this decision on Tuesday, at the start of the evening. The Center Pompidou should thus return a painting by Marc Chagall and the Musée d’Orsay the only work by Klimt that it possessed.

“Historical”, this is how the Minister of Culture, Roselyne Bachelot, described the bill, by which fifteen works, including paintings by Gustav Klimt and Marc Chagall, will be able to be returned to the heirs of Jewish families . plundered by the Nazis .

“This is a first step” because “looted works of art and books are still kept in public collections – objects that should not, that should never have been there”, underlines the minister.

Long accused of being behind several European neighbors in terms of reparation, France reached a major milestone on Tuesday, February 15, with this vote in the Senate which authorizes the State to return these works of art to the heirs of despoiled families. . After the National Assembly which had given its consent on January 25 , the green light from the senators was the last step before a restitution.

Research on the ownership of spoliated works is accelerating

Legally entered into the French national public collections by acquisition, these works come under the movable public domain protected by the principle of imprescriptibility and inalienability. Their restitution therefore requires a law making it possible to derogate from this principle.

This vote in Parliament makes it possible to take a further step towards a more comprehensive “framework law”, which would facilitate restitutions in the years to come by simple decree of the French government, without the need to go through a case-by-case authorization from the legislator.

For thirteen of the fifteen works concerned by the vote in the Senate, the beneficiaries were identified by a Commission for the compensation of victims of spoliation (CIVS) , created in 1999 in the wake of Jacques Chirac’s speech in 1995, during the commemoration of the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup. The then president recognized the participation of France in the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis. Before that, the issue of restitution was passed over in silence for a long time, until the fall of the Soviet bloc and the opening of new archives.

The creation of a research and restitution mission for cultural property looted between 1933 and 1945 within the Ministry of Culture two years ago has strengthened this system. It has made it possible to accelerate essential research on the provenance of spoliated works in order to facilitate their restitution.

No doubt at the time of the acquisition of the Klimt by France

For the “Rosiers under the trees” by Gustave Klimt, kept at the Musée d’Orsay and the only work by the Austrian painter belonging to the French national collections, it took more than 20 years of research before making the link with its owner Eléonore, known as Nora, Stiasny. This Austrian Jew, from a family of collectors, had sold it during a forced sale in Vienna in 1938, during the Anschluss, before being deported and murdered, like her mother, her husband and their son, as well as other members of their family.

The painting was acquired in 1980 by the French State for the Musée d’Orsay, from a gallery in Zurich, which held it from a then unidentified owner who turned out to be Herta Blümel. At that time, explains the Ministry of Culture , the research undertaken before the acquisition, as well as the publications of the time or the contacts made with the members of the family of Nora Stiasny, “had not raised any doubt on the history of the work, nor suggested a link between the work and Nora Stiasny”.

But the information gathered in recent years has made it possible to identify an old acquaintance of Nora Stiasny: Philipp Häusler, an arts teacher and Nazi militant, who had not hesitated, in 1938, to buy the canvas “at a low price”. . The wife of the latter is none other than Herta Blümel, by whom the “Rosiers under the trees” landed in a gallery in Zurich, where the French State bought it.

The heiress of the Chagall painting was unaware

Another terrible story, that of the painting by Chagall, entitled “The Father”, kept at the Center Pompidou and entered the national collections in 1988. It was recognized as the property of David Cender, a Polish Jewish musician and luthier, who settled in France after escaping death in Auschwitz.

The canvas was seized in 1940, when David Cender was forced to leave his apartment for the Lodz ghetto, before being sent to a concentration camp, where he lost his two-year-old daughter, his wife in her forties years, as well as his mother and two sisters. The only survivor with his brother, Cender had during his lifetime taken steps to find his painting, but he had not spoken to his descendants with whom he did not discuss this painful past, explains his heiress, his little niece Orna, in the columns of the JDD .

In 1959, David Cender seized a commission created in Germany for the restitution of works of art stolen from Jews. But it was only after his death that a German court recognized him as the owner of the painting and certified that it had been stolen. In the meantime, “The Father” was recovered by Marc Chagall and the painter’s heirs donated it to the National Museum of Modern Art (Centre Pompidou) in 1988.

Orna had not heard of this case until a phone call in 2015, telling her that she was the heiress of the Chagall painting. The 60-year-old was just 11 when David Cender died in 1966, taking with him the secret of his quest.

“Asking for compensation implies that the victims are still alive or that their heirs know of the existence of an economic spoliation suffered by their grandfather. However, the difficult intra-family transmission of the hardships of the Occupation, mentioned by the historian Simon Perego, often forced the following generations to live in total ignorance of the family past, which has sometimes become taboo”, explains historian Johanna Lehr in an op-ed published in Le Monde , where she recalls that half of the cases of spoliation of Jewish property in France – works of art included – remains to this day uneducated. In the case of David Cender, it was a company specializing in the search for spoliated works of art, Mondex, which made the connection with the heirs.

Among the fifteen works soon to be returned are also eleven drawings and a statue kept at the Louvre Museum, the Orsay Museum and the Château de Compiègne Museum, as well as a painting by Utrillo kept at the Utrillo-Valadon Museum (“Carrefour à Sannois”).

Do justice without waiting to be seized by the families

Nourished by works confiscated by the Nazis, the art market flourished in Paris during the Second World War, as several specialized historians tell us. In France, 100,000 works of art were seized during the 1939-1945 war, according to the Ministry of Culture. “Many Jewish families, victims of anti-Semitic measures, were forced to sell their property from the end of 1933, in Germany. In France, when the sale was organized by the Vichy regime, many archives remained but when it these were private sales, there were no traces, the works ended up on the art market”, also recalled David Zivie, head of the ministry’s research and restitution mission for spoliated cultural property. of Culture, during a hearing by the senators in January.

While some 45,000 looted works of art were returned at the Liberation, around 2,200 were selected and entrusted to the custody of national museums. Say “MNR” works (for National Museum recovery), these are recognized as looted objects, they do not belong to the French State, they are just on deposit in museums while waiting for their owners to pick them up. These MNR objects can be returned by a simple administrative decision, which is not the case for these fifteen works for which a tailor-made law was needed.

About 13,000 other works returned at the Liberation were sold by the administration of the Estates in the early 1950s. Many looted pieces thus returned to the art market.

The Commission for the Compensation of Victims of Spoliation, assisted by the Mission for the Search and Restitution of Spoliated Cultural Property, can now seek justice without waiting to be seized by the families of the owners of spoliated works of art, and this with the support of Parliament.