INVESTIGATION | The estate of Margret Kainer, who died in France in 1968, is at the heart of a dispute between her distant heirs and the local authorities, who are accused of stealing her fortune. Also at stake are the masterpieces she was once robbed of by the Nazis.

In her passport photo, Margret Kainer smiles shyly at the photographer. On the left-hand page, it reads: “Kainer, née Lévy, Marguerite, born January 26, 1894 in Berlin (Germany), 157 centimeters, brown hair, brown eyes.” The young woman is German, but the document, dated 1946, is Swiss and written in the three languagesofthe Swiss Confederation. Another period image shows her posing, chin resting in the palmofher right hand. Her Louise Brooks bob- style haircut and the fur on her shoulders make her look like a Hollywood star. In fact, she was rich, very rich: When he died in 1928, her father Norbert Lévy, a Berlin businessman and art collector, bequeathed his fortune to her.

Threatened by the Nazis’ rise to power because she was Jewish, the young woman left Germany with her husband Ludwig in 1933. They took refuge first in France, then, from 1942, in Pully, near Lausanne, Switzerland. Four years later, they obtained a Nansen passport, named after the high commissioner behind the document issued in Europe to refugees who were victims of persecution.

After the war, they returned to Paris. Ludwig Kainer (1885-1967), a painter and fashion designer, worked in the film industry, creating sets and costumes. The couple lived in the northwestern suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, where they counted Jean Cocteau and Josephine Baker among their social circle. They regularly extended their residence permits but promised the Swiss authorities they would settle permanently in the Swiss Confederation in order to keep their Nansen passports. They never did. Margret only declared an address later in life to ensure the document’s renewal.

Then came 1968, the year she died at the age of 74, a widow with no children or identified heirs. By court order, her fortune, estimated at around 17million Swiss francs, was divided into three: 6.3 million francs for the municipality of Pully (near Lausanne), where she was registered at the time of her death, although she no longer lived there; 6.3 million for the canton of Vaud, to which the chic city of Pully belongs; and 5 million for the Norbert Stiftung, a foundation intended to preserve the memory of her father. According to an official document from the municipality of Pully, dated March 30, 2005, and unearthed by Le Monde, Norbert Stiftung had previously “filed a claim on the entire estate of the late Margret Kainer,” but an agreement was eventually reached between the three entities. No one had any objections.

‘Complicity with the regime’

Fifty-six years after her death, the case has not yet been settled, and may even reach a surprising conclusion in the coming months before a Lausanne court. For the past 10 years, the Mondex Corporation, which specializes in the recovery of dormant assets, has been handling the case. The company, paid by clients in the form of fees, was founded by a Canadian, James Palmer, who believes that the three-way division of the inheritance constitutes “plunder” to the detriment of Kainer’s descendants.

Officially, she had no heirs. But in 2014, Palmer and his team of historians, lawyers and researchers claimed to have found 10 or so heirs across Europe, Canada, the United States and Australia. They are the grandchildren of the millionaire’s cousins. They are determined to defend their interests. “My father and grandparents are Holocaust survivors,’ wrote one of them in a letter sent to Le Monde by Mondex. “All light must be shed on the banks, institutions and authorities who took advantage of people like my cousin’s grandmother. Their apathy, silence and greed are a form of complicity with the Nazi regime, as if they wanted to erase all trace of Margret and her family.” Two siblings from the Netherlands added: “We’d like the Swiss authorities to put themselves in our shoes. Imagine what it means for families to be

deprived oftheir history, culture and possessions.”

Indeed, Switzerland has undertaken some research in the past, but according to the heirs’ lawyers, these efforts were not thorough. “One might wonder about the seriousness of the efforts made at the time to find the heirs, given that a private company succeeded in doing so on the basis of open-source information,’ quipped lawyer Francois Zimeray. The Parisian lawyer represents certain members of Kainer’s family. “It remains indisputable that these communities would never have been the beneficiaries of this wealth had it not been for the persecution of European Jews, and in particular that of a family decimated and dispersed by the Nazis,” he added, referring to two of the beneficiaries, the municipality and the canton.

According to Zimeray and Mondex, the Fondation Norbert, which is intended as a continuation of the Norberstiftung created by Norbert Lévy in 1927 to support his family, is a “bogus” institution. “Lévy’s will specified that if his daughter died after her husband and without descendants, the family foundation was to cease to exist,” they claimed. “A new one was to be created, intended to help family members in need. It was to bear the name ‘Norbert Levy Stiftung,’ be based in Berlin, be run by the Jewish community and receive three-quarters of the estate.”

‘The tip of the iceberg’

When Kainer died in 1968, things didn’t go according to plan, at least according to Mondex. “At that time,’ it explained in a written document, “the family foundation had only one board member, Dr. Albert Genner, director of UBS Bank. Instead of acknowledging the dissolution of the foundation, he wrote an internal memo recommending the creation of a charitable foundation.” This foundation was set up in Chur, Switzerland, not in Berlin; it was not run by the Jewish community and did not benefit the Levy-Kainer family. “Nevertheless,” continued Mondex, “it adopted the name Norbert Levy Stiftung and was issued a certificate of inheritance from the estate. The name of the dummy foundation was then changed again, erasing any reference to Norbert Levy’s last name, as well as Margret Kainer’s maiden name.”

When contacted by Le Monde, Norbert Stiftung, through its lawyer Christian Girod, replied: “The foundation, which supports the schooling of Jewish children in Switzerland, was properly established in accordance with Norbert Levy’s wishes and entered in the commercial register. We contest all of the

allegations made against us and reserve our statements for the court. We will not argue with them in the press.”

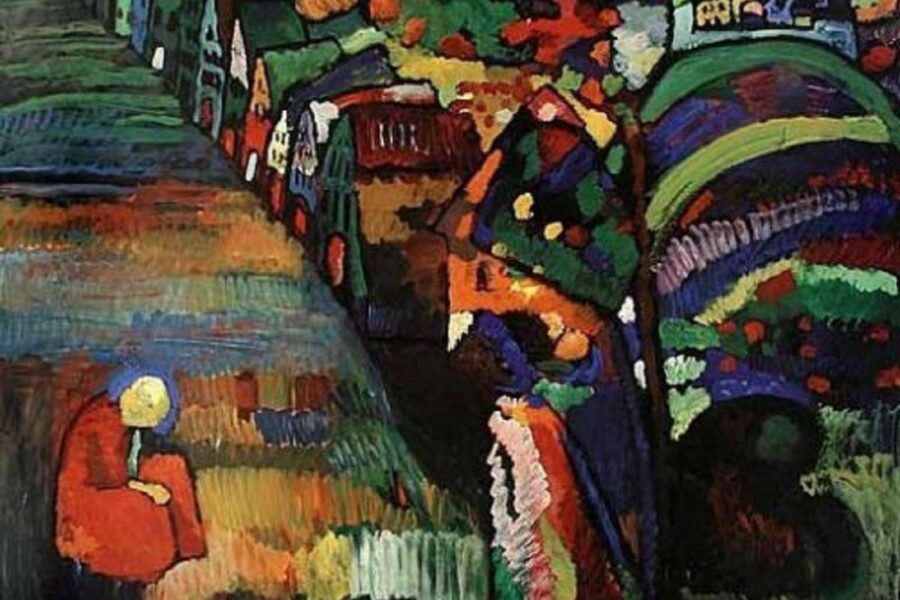

The Kainer inheritance case is not just a question of dividing up money. It also concerns the recovery of works of art stolen by the Nazis. In 2005, the canton of Vaud and the municipality of Pully granted the Fondation Norbert the sole right to take legal action to recover the property stolen from Kainer. This time,

experts are talking about a fortune approaching 50 million Swiss francs. This includes a painting by Edgar Degas, stolen from the Levys and sold at a Christie’s auction in New York in 2009 for $10 million (€9.2 million). “No doubt the tip of the iceberg,’ said Mondex. Two years ago, a work by Pablo Pissarro, also stolen by the Nazis, went on sale in New York for $1.8 million. The Kainer family then sued the owner, who was finally allowed to sell it after a settlement.

For their part, Pully and the canton of Vaud are defending themselves by putting up a united front. “The most we can do is point out that the state and the municipality have not ‘posed as heirs, which is not their role, but that they have been recognized as such by the Vaud courts,” wrote Jean-Luc Schwaar, director general of the canton’s department of institutions, to Le Monde. The two communities pointed out that Swiss law stipulates that, in the absence of legal heirs, the estate reverts to the canton or municipality of the deceased’s last residence. The opposing party replied that Margret Kainer had kept her Swiss residence for administrative reasons, but in reality, she was living in Paris and no longer had any links with Switzerland.

From legal rights to moral obligations

In strictly legal terms, the heirs’ lawyers are aware that victory in court is far from a foregone conclusion. In 2002, the Vaud court ruled on Kainer’s place of residence at the time of her death and is unlikely to reverse its decision today. Instead, they are trying to frame the debate on moral grounds. “When a

museum or a state decides to return a work of art, it’s first and foremost a question of principle,” explained Zimeray. “Even if Vaud and Pully acquired the estate in good faith, now that the existence of heirs is known to them, can they in good conscience refuse to return it? This inheritance should be painful for them, given its tragic origins.”

In the meantime, Palmer, founder of Mondex, wrote to the president of the Vaud canton’s governing body and to the mayor of Pully. The letter, dated December 4, 2023, was also sent to a dozen figures, including Alain Berset, then president of the Swiss Confederation, to remind them of Kainer’s story:

“The Holocaust decimated her family and the few survivors were scattered across the world. It was these circumstances that enabled Pully and Vaud to acquire the inheritance. (…) Continuing to hold Margret Kainer’s estate in the presence of known heirs now seems hardly sustainable.” The Canadian and French lawyers also mentioned that, on November 22, 2023, the Swiss Parliament decided to set up an independent commission to deal with cases of cultural property confiscated during the Nazi era. They hope that this commission will take up the case ifan out-of-court settlement proves impossible, or if the Vaud court rejects their request.

These arguments don’t seem to faze the canton and the municipality. To prevail, they intend to invoke the statute of limitations on the heirs’ claims and point out that Kainer died 56 years ago. The mayor of Pully, Gil Reichen, warned in the newspaper Le Temps: “We’re not going to give up millions without even being certain that the claimants are indeed heirs.” As for the Fondation Norbert’s lawyer, he intends to ask that all the plaintiffs’ claims be rejected.

For their part, Kainer’s heirs do not rule out finding a compromise, even if it means not recovering the entire fortune. They know they risk being turned down: The two entities could always argue that, even with the best of intentions, the restitution of 6.3 million Swiss francs each is impossible. It’s an argument that amuses one of the heirs’ lawyers: “Pully is one of the wealthiest municipalities in the region. And the canton’s taxpayers include companies like Nestlé, the world’s largest food group. We should be able to find money in this part of Switzerland, if we have to.”

By Alexandre Duyck

Translation of an original article published in French on lemonde.fr; the publisher may only be liable for the French version.