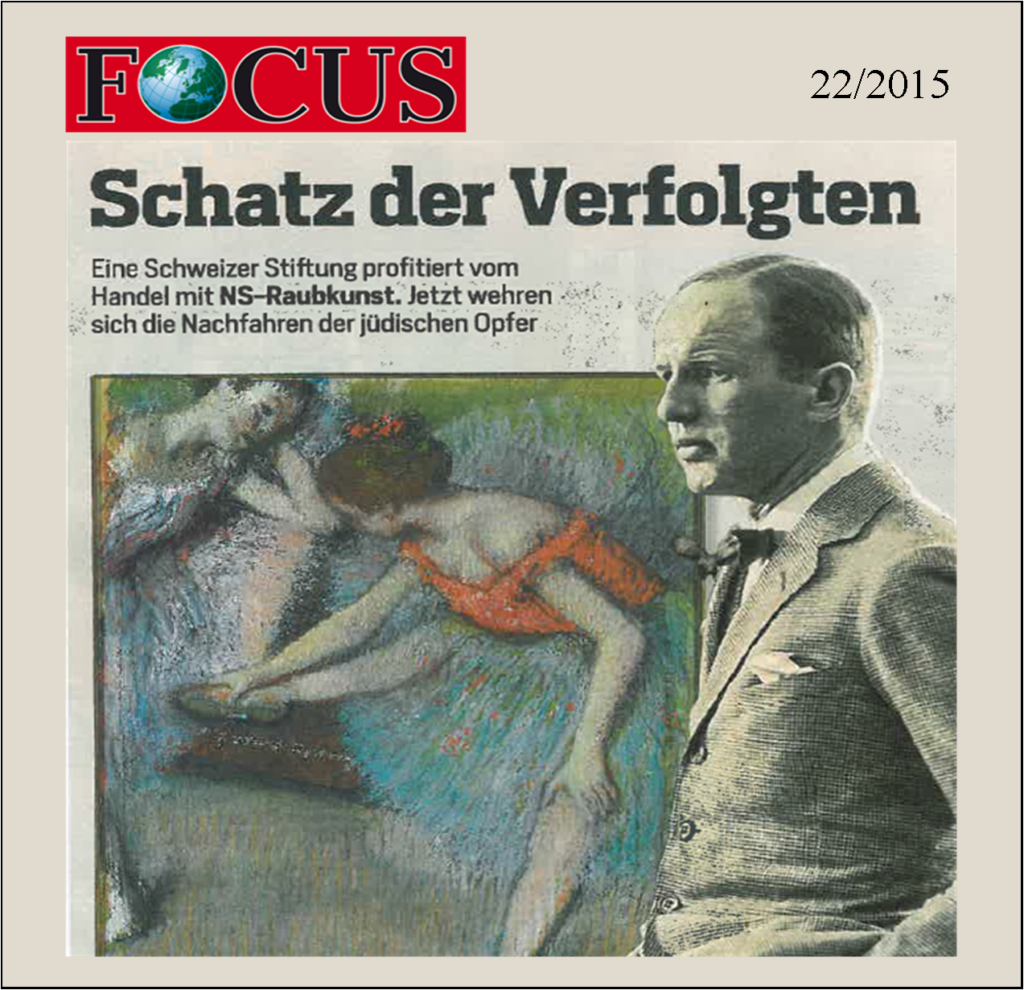

CULTURE & MEDIA

The Treasure of the Persecuted

A Swiss foundation is profiting from the

sale of Nazi looted art. Now the

descendants of the Jewish victims are fighting back.

[photo]

Auctioned off for 11 million dollars The “Dancers” by Edgar Degas

Both young ballerinas seem to be relaxing. They come across dreamily, self-engrossed—and yet completely together. They spend the few minutes between scenes amongst only themselves. Nothing touches them. No happiness, no fear. Even the gaze of the artist, who conjured them up on his canvas long ago, doesn’t bother the women. The “Dancers” by Edgar Degas have been dreaming in their gossamer pastel cosmos now for almost 120 years.

And yet they have a part in a drama. It’s about escape, theft, and a search for the inheritance of a multi-million dollar treasure. And above all it’s about the truth—that, all too often, would be too easy and which as is yet even more often the case, is easily covered up.

The famous Christie’s auction house auctioned off the Degas in 2009 formerly eleven million dollars. In the auction catalogue, Christie’s customers could read that the painting first belonged to the German-Jewish Kainer couple, who lost their home in Berlin, their possessions, and even their famous art collection during the time of the Nazis.

The painting, the auction house assured, was only being auctioned, because they were able to reach an “agreement” with the estate of Ludwig and Margret Kainer. In plain terms: The descendants of the legitimate owners were compensated. All’s well? Everything legal and above board?

Almost nothing is good and above board with “looted art”—those thousands and thousands of treasures that Hitler’s henchmen stole from disenfranchised and persecuted Jews. For decades, buyers and sellers on the worldwide art market weren’t interested in whether any painting that could be snatched up came from brown [fascist] stolen art. Moral standards and some rules of the game have only been in effect for about 20 years.

In principle. For example, the Bavarian justice system hid the legendary art treasure of the Munich hermit Cornelius Gurlitt for over a year. Only after FOCUS uncovered the case did the federal government start the search for the legitimate heirs. A few days later, the first painting from the Gurlitt estate, the “Sitting Woman” by Henri Matisse, was finally able to be returned to the descendants of the former Jewish owners.

The deal surrounding the “Dancers” by Degas, in comparison, proceeded quickly and honestly. At least it appeared to. In reality, no individual descendant of the Kainers—and there are dozens of them—received a cent for the impressionist masterpiece.

Christie’s so-called “inheritance” is a foundation, founded and run by employees of a Swiss bank. It is this foundation that profits again and again, whenever a work of art from the Kainer collection finds a new buyer. No matter if a Renoir, a Monet, or an ancient Egyptian artefact is being auctioned: If it once belonged to the Kainers, the foundation receives money. The business model is simple: the Kainers built up a world-class collection and hundreds of their works of art could turn up at auctions.

Several years ago the foundation had to defend their claims—against a community (Pully) and a canton (Waadt) in Switzerland. The disagreement was quickly mediated. Community, canton, and foundation recognized that really no one could assert a claim to the complete inheritance. So they divided up the fortune up to that point, approximately 17 million Swiss francs. It had to be clear to all of those involved at the time that the Kainers had never resided in Switzerland.

No one thought to ask the relatives of the Kainers. Even those who attribute only the best intentions combined with strong business acumen to the foundation are unable to deny that Jewish victims of the Nazi regime were being posthumously robbed, for the second time in this case.

That should come to an end. Several descendants of the Kainers have taken up the fight for the inheritance, which is valued at as much as 50 million dollars. They filed a suit in New York to challenge the sale of the Degas painting. They’re filing suit in Switzerland—and, in particular, they are filing suit in Germany.

In 1972 a Berlin court issued the Swiss foundation a certificate of inheritance. According to information obtained by FOCUS, the Berlin Court of Appeals will take on the Kainer case this year and shine some light on a dramatic occurrence that also started there.

Margret Kainer was born in 1894 in Berlin as the only child of the Jewish Councillor of Commerce Norbert Levy, who resided at Kurfürstendamm [a famous avenue in Berlin] and became wealthy through the metal trade.

CULTURE & MEDIA

In 1923 Margret married the physician and set designer Ludwig Kainer. Margret’s father died in 1928. The Kainers were on vacation when Hitler came to power in 1933. They never returned to the German Empire. The National Socialists confiscated all of their assets—among them also the already legendary art collection.

The Kainers, who had no children, lived as stateless refugees, largely in France. After the fall of Hitler’s empire they fought for years to win back their property. But the legal battle with the state of Berlin took too long. Ludwig Kainer died in 1967 followed by his widow one year later.

Others joined in the hunt for the Kainer treasure. Albert Genner, a director of the then Union Bank of Switzerland, remembered Norbert Levy and came up with a plan. Levy had once established a foundation, which was supposed to support Levy’s relatives and in fact proved to be important for the survival of the daughter during the years of the exile. By 1944 the foundation’s resources were exhausted. As late as Margret’s death the foundation was defunct.

But the banker Genner, as he recorded in a “private” note from December 21, 1970, decided to bring the foundation back to life—to re-found it—in order to “construct” a claim on the inheritance.

In February of 1971 Genner established the Norbert Levy foundation (later renamed to the Norbert foundation) in Swiss Chur. The charitable institution was allegedly supposed to support young Jews in need. But its actual mission was quite different. In order to get to the Kainer estate confiscated during the Nazi years, Genner needed a legally confirmed hereditary title. That is precisely what the District Court of Berlin certified the Norbert Levy foundation with on December 18, 1972 by the issuing of a “partial certificate of inheritance” for the estate of Norbert Levy.

Art detective

The Canadian James Palmer specializes in the establishment of inheritance claims for works of art. He organized the legal offensive of several Kainer descendants.

Under fire

An employee of the Swiss bank UBS manages the foundation, which up to now has been acting as heir to the Kainers.

How this remarkable decision came to pass is no longer clear. The court documents have apparently disappeared. Lawyers working for the Kainers suspect that the Berlin judges simply didn’t recognize the fact that the foundation was being re-founded.

The certificate of inheritance turned out to be the key to the treasure. Meanwhile the foundation is said to have collected over eleven million dollars.

Several relatives of the Kainers have hired looted art specialist James Palmer to work for them. The Canadian art detective, with the lawsuits in Lausanne and New York, is also taking aim at the Swiss bank UBS.

Background: The Union Bank of Switzerland was absorbed in 1998 by UBS in a merger. A manger of today’s UBS has worked as president of the Norbert foundation for 25 years. His private address has served as foundation headquarters for some time and, UBS explained, the bank plays no role in any of the foundation’s activities.

UBS was one of those Swiss banks that found themselves exposed in the 1990s by the accusation of not wanting to release the assets of Jewish victims’ families deposited with them. Only when threatened by a general boycott of Swiss products in the United States did the banks gave in.

It may be that this fiasco is not quite forgotten at UBS—and that the sight of the “Dancers” by Degas troubles many a banker.

MARKUS KRISCHER

FOCUS 22/2015

Photos: Wolf Heider-Sawall for FOCUS Magazine, Martin Ruetschi/Keystone